The story of how I paid off $60,000 of student loans in two years: Part 2

If you have student loans, maybe sit down for this one.

Hello -

This story will make more sense if you read Part 1.

The Fine Print and the Fury

After I made my $5,000 grief-fueled lump sum payment, I lingered on my loan servicer’s website and took a look around. I wasn’t on this site much. I had autopay set up, so I never really had to be.

I saw this dashboard that showed how much I still owed – $54,000 – a laughably high number. (To be clear, I really tried to be smart about taking out this debt. I only applied to one-year graduate programs because I didn’t want to be out of the workforce for two. I got into both Columbia and Northwestern but chose Northwestern because I received a $20,000 scholarship and I knew the cost of living in Chicago would be lower).

The monthly payment that was withdrawn from my checking account to pay this debt each month was manageable (I was on an income-based repayment plan).

In my mind, the fact that that money was leaving my bank account each month meant I was “paying down my student loans.”

But a closer look at my payment history showed me something else:

The payments I was making each month were mostly going toward the interest I was accruing, not the principal.

So even with the last three years of monthly payments, I had been barely making a dent in paying down my loan.

INTERESTING

To fully appreciate how this can happen, let’s compare the U.S. system to another country’s: the Netherlands.

In the U.S., federal interest rates currently range from 6.53-9.05 percent. Private student loans can range from 4-17 percent and can often be variable, meaning people can sign up at 4 percent and find themselves paying 7, 12, 17 percent interest in subsequent years.

In the Netherlands, for a long time, you’d pay 0 percent interest for student loans if you pay them back within 10 years! They recently raised interest rates from 0.46 percent to 2.56 percent, to much outrage.

It’s hard to appreciate the difference between 6.53 and 2.56 percent, so let me just take you through this exercise using Google’s loan calculator.

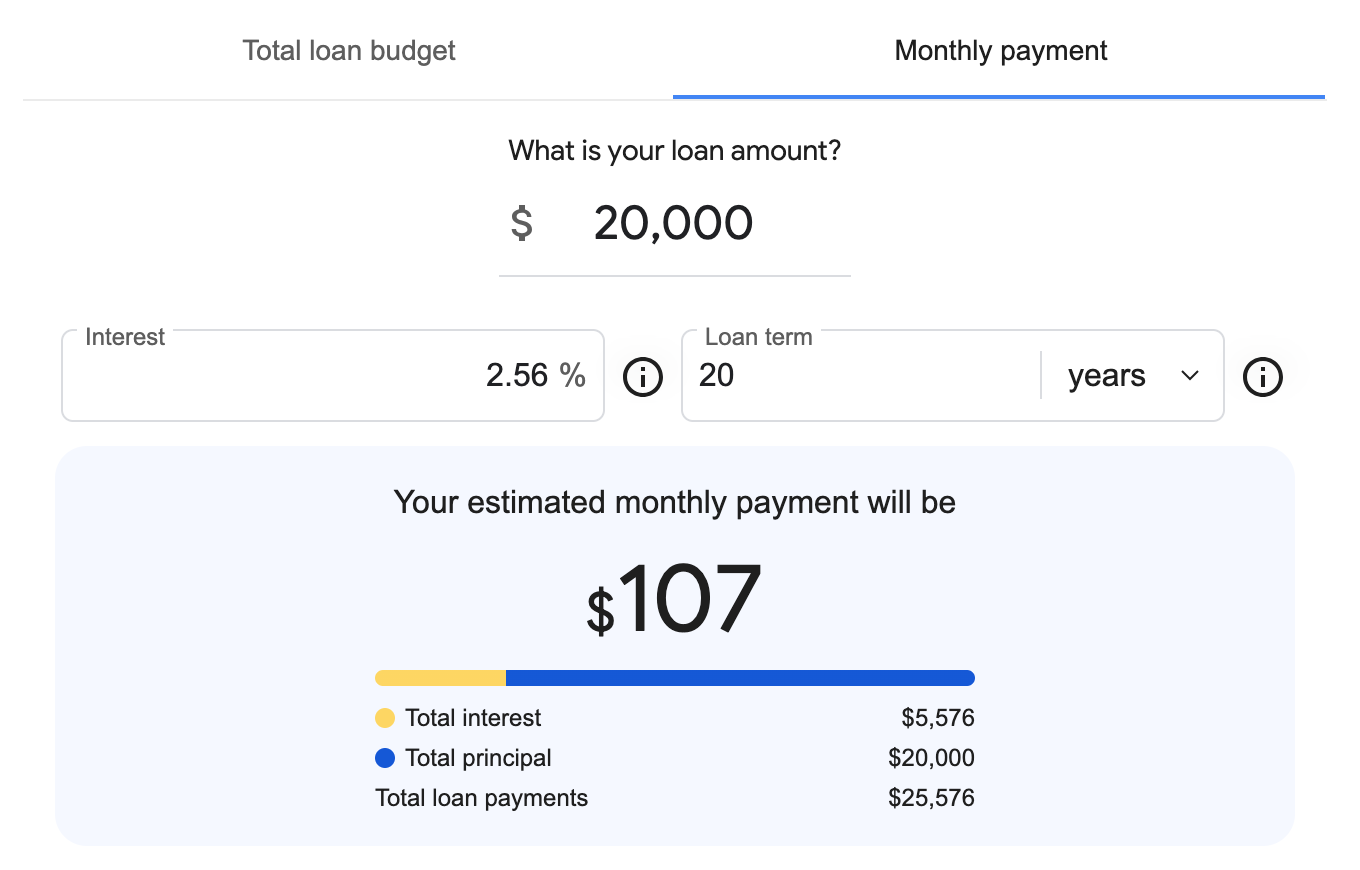

Let’s say you’re a borrower in the Netherlands today and owe $20,000 at 2.56 percent interest.

Over the course of 20 years, you’d pay:

$20,000 in principal

$5,576 in interest

With a $107 monthly payment

In the end, you’d have paid $25,576 for a $20,000 loan.

If you can manage to pay a slightly higher monthly payment, $190 dollars, you can pay off the loan in 10 years and pay $2,691 in interest along with your $20,000 principal, so $22,691 for a $20,000 loan.

Now let’s say you’re a student loan borrower in the good ole U.S. of A.

Let’s say you’ve borrowed the same amount of money, $20,000, at the lowest current federal interest rate, 6.53 percent.

Over the course of 20 years, you’d pay:

$20,000 in principal

$15,873 in interest ($10,297 more than if you lived in the Netherlands)

With a $150 monthly payment

In the end, you’d have paid $35,873 for a $20,000 loan.

If you can manage a higher monthly payment, $228 dollars, you can pay off the loan in 10 years and pay $7,289 in interest along with your principal, so $27,289 for a $20,000 loan.

Now let’s say you’re a U.S. student loan borrower with interest payments at the HIGHEST END of the current federal range: 9 percent.

After 20 years you’d pay:

$20,000 principal

$23,187 in interest

With an estimated $150 monthly payment

In the end, you’d have paid $43,187 for your $20,000 loan. The amount you’ve paid in interest will have exceeded the amount you borrowed to begin with.

If you can manage a higher monthly payment, $180, over 10 years you’d pay $10,403 in interest plus your $20,000 principal, so $30,403 for your $20,000 loan:

At the end of the day, I live in a country where the government is, on the one hand, creating a way for its citizens to fund their educations, typically under better terms that private lenders can offer.

I also live in a country that is still making a substantial amount of money off of me and my peers via interest. More money than other comparably wealthy countries collect from their student loan borrowers, if those countries collect interest at all. Our neighbors in Canada eliminated interest payments on student loans on April 1, 2023.

Acceptance, plus a heaping spoonful of spite

Back in front of my laptop in 2018, the realization about my interest situation sent me spiraling. I felt so stupid. I was angry at myself for not fully processing how much those single-digit interest rates could add up to be.

I could, and did, and do, dream of ways the system could change. I could’ve thrown up my hands, declared the system rigged, continued paying the minimum amount, and put my hope in U.S. politicians to overhaul it all. (If you feel that way, I get it and fully acknowledge that that hope did pay off for many borrowers who badly needed the relief).

As I said in part 1, financial decisions are a function of values and circumstances.

Here were mine:

I was a realist living in 2018 benefitting from her graduate education with gainful employment in her field. Even though I had been working for a public media organization at the time, I knew that qualifying for public service loan forgiveness was notoriously difficult (Biden did make it easier for people) and would limit my career flexibility over the following 10 years. While I was angry about the U.S.’s interest policy, my anger wouldn’t meaningfully change anything for me and my interest rates in the short term.

So I decided to accept two realities of the game I’d been playing:

I am on the wrong side of compounding interest.

The only thing I have any control over is how much interest the government is going to be able to make off of me in the end.

And that, readers, is the state-of-mind that began my entirely spite-fueled mission to pay off this debt as soon as possible.

And so, I entered into Google:

“How do I pay off my student loans as soon as possible?”

And I found an answer.

More on that next week.

One final note on interest

This Forbes article explains that U.S. interest rates for student borrowers are based on “the high yield of the 10-year Treasury note at auction, a process established through Congressionally-enacted statute.” Pegging it to the Treasury note, as we’ve seen, is just a policy choice. It’s a game rule that can change.

Meanwhile, this fall, even in the age of the Biden administration’s debt forgiveness policies, U.S. students are out there, borrowing money for bachelor and graduate degrees at 6.53-9 percent interest.

ETC.

Dutch artist pays his debt with a tapestry about his debt - NL Times

Is Rising Student Debt Harming the U.S. Economy? - Council on Foreign Relations

How college became so expensive - CNBC